A “Bee-g” Question: How do Honey Bees and Native Bees Interact?

Access to clean, nutritious forage is essential for all bees, and as bee forage is declining each year in the USA, the number of native bees and managed bees are also declining. 75 years ago there were nearly twice as many honey bee colonies in the US, and more than half the native bee species assessed seem to be in decline.

Less habitat and forage availability increases potential for resource competition, and as bee health concerns are top of mind, many questions arise about whether bees create pathogen pressure by transmitting diseases while foraging. Concerns about native bee vulnerability and habitat scarcity have brought efforts to exclude honey bees from some forage and pastures. Such policies could have far-reaching effects on an already strained beekeeping industry, and also pits bees against each other.

Project Apis m. and Costco USA are supporting a multi-year project to study honey bee and native bee interactions, to increase the science in this area and also learn more about how to improve and manage habitat for the benefit of many bee species.

We recently visited the project at the USDA-ARS Native Bee Lab in Logan, Utah. This lab, which is home to both Apis (honey bee) and non-Apis experts, is uniquely able to study several bee species closely in a variety of lab and field conditions. This is a very complex project involving technology to measure and track several species of bees’ behaviors and reproduction, enclosures with engineered habitats to evaluate plant species’ use by various pollinators, and field sites characterized with and without managed honey bees.

This project aims to study interactions between bee species and measures of health:

- competition and behavioral changes (including foraging behavior)

- pathogen transmission and symptoms or effects of pathogens in different species

- overall health and strength of bees

- brood rearing and reproduction

- forage utilization, both in natural and engineered habitat

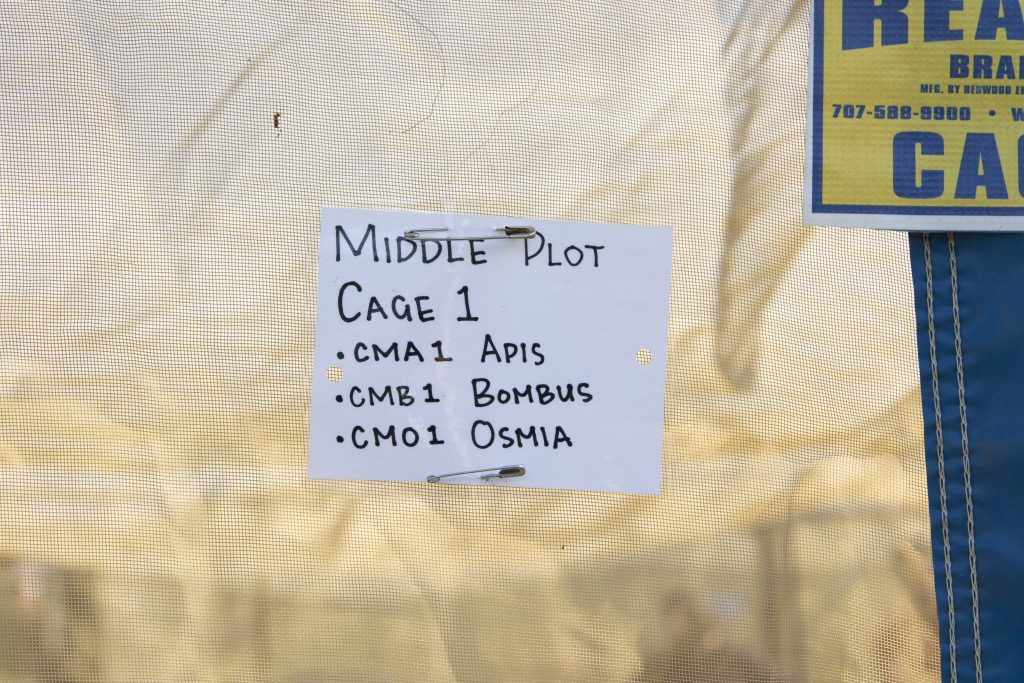

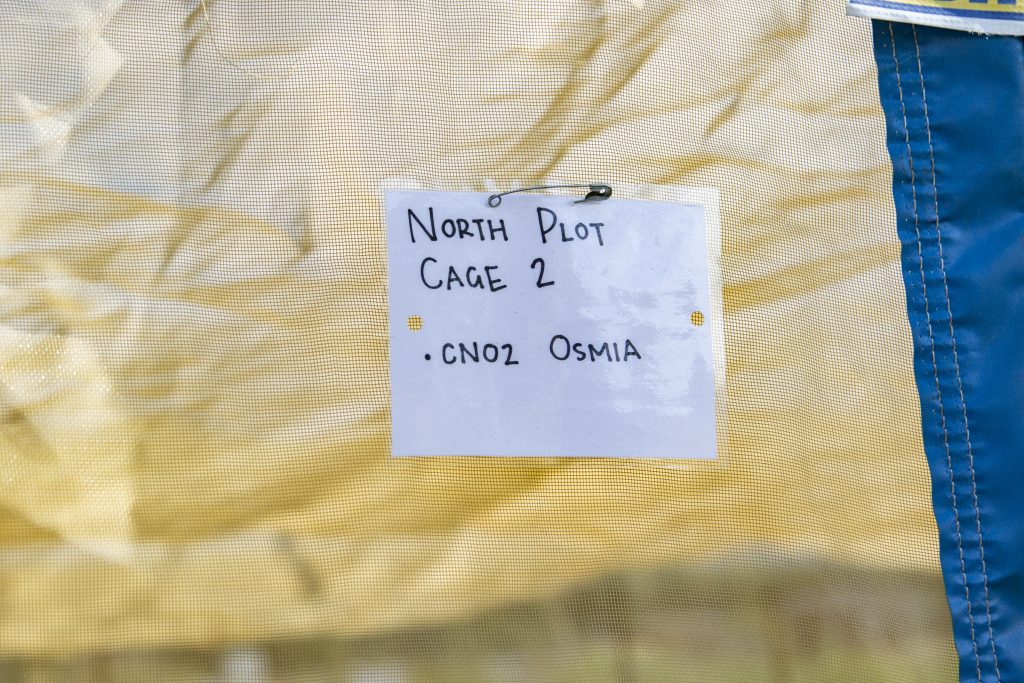

Using three different locations and trials, a variety of bee species and floral settings are being observed. In one trial, several large screen houses contain different combinations of bee species and floral resources, which are monitored using cameras, x-rays and traffic gates.

A second trial is conducted at a screen house containing mason bees with a honey bee colony located outside of the screen. The honey bees are allowed limited access to the screen house so data can be collected in the same environment with and without the presence of honey bees.

In a third trial, honey bee, bumble bee and mason bees are placed on public lands in the Cache Valley in a grazing and recreational area. In addition to monitoring the bees, transects are surveyed for floral resources, and native bee surveys are conducted. These locations have a long history tracked by Darren Cox, of Cox Honeyland, who helped conceive the project, and provided the honey bees and locations for this trial.

An unexpected discovery in the first year of field trials was that almost all of the managed bumble bee colonies (Bombus huntii) were parasitized and killed by a kleptoparasitic bumble bee, Bombus insolaris. This discovery led to a publication and the knowledge that excluders can be used to protect managed bumble bee colonies from parasitism by Bombus insolaris.

The robust presence of Bombus insolaris is thought to reflect an equally robust population of other bumble bee species in the area. This, along with genetic evidence, could suggest the honey bee colonies present in the area did not negatively impact the success of the native bees in the area, though as the authors state in the publication, more research is needed to fully understand the relationship between honey bees and native bees interacting on the landscape.

This blog was originally posted on 9/31/2021, and shared here (with permission) for the Bee Health Collective audience.

Authors: Sharah Yaddaw, Communications Director, Project Apis m.

Danielle Downey, Executive Director, Project Apis m.

References:

(1) VanEngelsdorp, Dennis & Meixner, Marina. (2009). A Historical Review of Managed Honey Bee Populations in Europe and the United States and the Factors that May Affect Them. Journal of invertebrate pathology. 103 Suppl 1. S80-95. 10.1016/j.jip.2009.06.011.

(2) USDA- NASS Honey Survey, 2021

(3) Pollinators in Peril, A systematic status review of North American and Hawaiian native bees Kelsey Kopec & Lori Ann Burd • Center for Biological Diversity • February 2017